A few years ago, as a Head of Department in a sixth form college, I took on the shared role of NQT (Newly Qualified Teacher) mentor for a new teacher, with a colleague from another academic department. Our approaches to mentoring were somewhat different. Whilst I interpreted the role as an opportunity to share what I knew about effective classroom practice and encourage the NQT teacher to question their own practice, my colleague saw it as a pastoral role in which they were responsible for checking on and ensuring the new teacher’s emotional and social well-being. We were probably a good team, in practice but the NQT teacher saw my approach, with a focus on classroom practice, as overly challenging and to quote ‘intimidating’. The particular practice which I challenged them about was their approach to feedback. Students in our shared classes were complaining to me that the teacher was setting lots of homework and assessed pieces but not returning for weeks afterwards or at all. I dealt with this by asking the teacher what they thought the purpose of homework and assignments was. They seemed somewhat surprised by this question and failed to come up with a satisfactory answer. I gently suggested that the purpose might be to improve and inform future work and help understanding. I further suggested that timing was crucial in the cyclical process of learning. If feedback is too distant from the particular assignment, homework or piece of learning, its effectiveness is reduced. If a student is to act on feedback it needs to be received in time to put into practice in the next assignment or piece of homework.

I watched the expression on the NQT teacher’s face as I told them this – it was like a lightbulb going on. They had clearly never considered feedback in that way. They had gone along with the procedures of the school and the traditional processes of teachers – teachers teach, they mark work and so on. I wish I could say that the teacher’s practice was changed radically – it did improve but they left teaching shortly afterwards.

Efficacy and feedback

I believe that the principle I was trying to establish with my NQT mentee is an important one – that feedback needs to be as close to and immediate to the learning activity as possible. This is where digital gaming has a lot to offer to the discussion. In digital games the emphasis is on the player experience. This experience is created in the relations between the affordances and constraints of the game and the player’s actions. Most digital games begin with a tutorial level.

In this tutorial level the player is exposed to the typical experience of the full game but given many ‘just-in-time’ prompts (see screenshot from ‘Call of the Sea’ game above) about how to access information, how to navigate the environment and how to succeed. They can practise what they have learnt immediately, in a low-stakes but real game environment until the player feels confident they have mastered it. Then they can progress immediately into the full game experience – the pace is dictated by the player in a way that is not usually possible for a student in the classroom. The lack of ‘continuity’ in the learning network (student-teacher-assignment-environment) caused by the constraints of the school timetable can also lead to a lack of engagement and participation in the learning process. Whether you believe engagement is important to learning or not, any disconnect between acquiring knowledge and applying it must tend to reduce the likelihood of that knowledge being retained.

There has been a tendency in education policy in England to place undue emphasis on outcomes and assessment criteria. Mansell, James et al., (2009) suggest that the uses to which assessment is being putting is now too wide. Although low stakes assessment or formative assessment can be a valuable tool for promoting future learning, giving feedback to students and their parents about their learning and helping their understanding and achievement, schools are under increasing pressure to use formative assessment to predict future outcomes and lower the risk of a poor inspection or poor league table rankings (Page, 2017). Formative assessment has, therefore, also become heavily influenced by external assessment criteria. Student feedback is largely concerned with how these criteria can be met (Torrance, 2017).

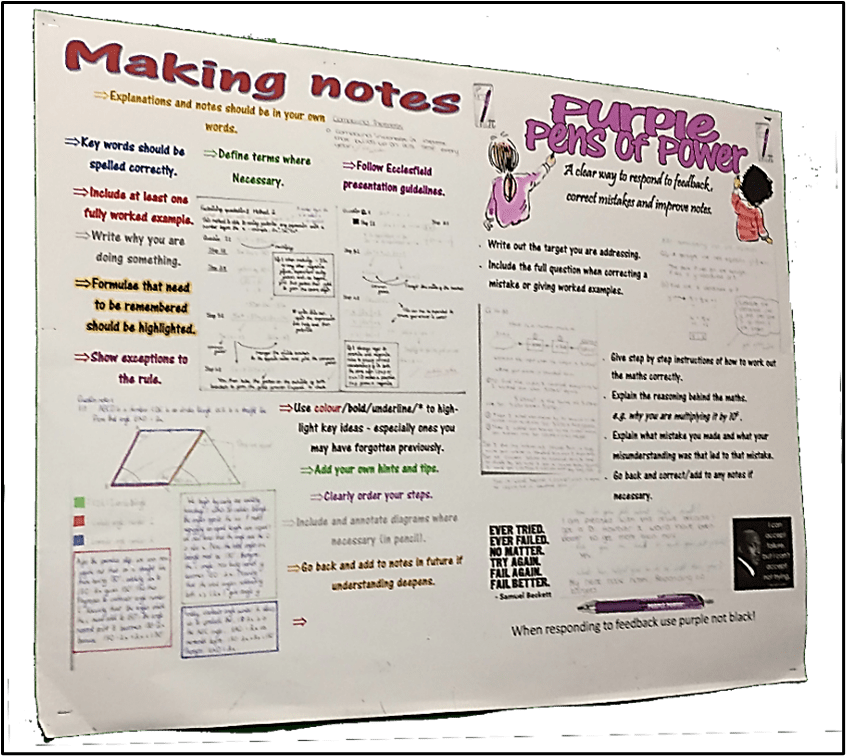

The emphasis on external assessment criteria has trickled down into the feedback and reflection practices prevalent in secondary schooling. Many secondary schools in England use a process called D.I.R.T or Dedicated Improvement and Reflection Time or Directed Improvement and Reflection Time. In D.I.R.T sessions, students receive their work (usually written) back from the teacher and are encouraged to reflect and write targets and make improvements to that piece of work. In principle, this sounds ideal – dedicated classroom time in which students are encouraged to reflect on work and improve it. In practice, this experience can be very different. It has become an over-regulated activity in which different coloured pens feature heavily, a formulaic and meaningless process, both for teachers and students.

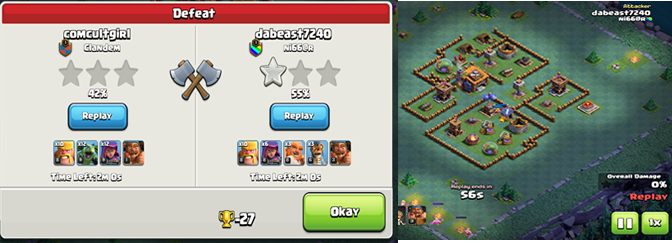

One of the clear differences between D.I.R.T sessions and feedback in games is that D.I.R.T sessions are triggered by the return of a piece of assessed work rather than self-recognition of failure to achieve a goal or acquire a skill in a digital game.

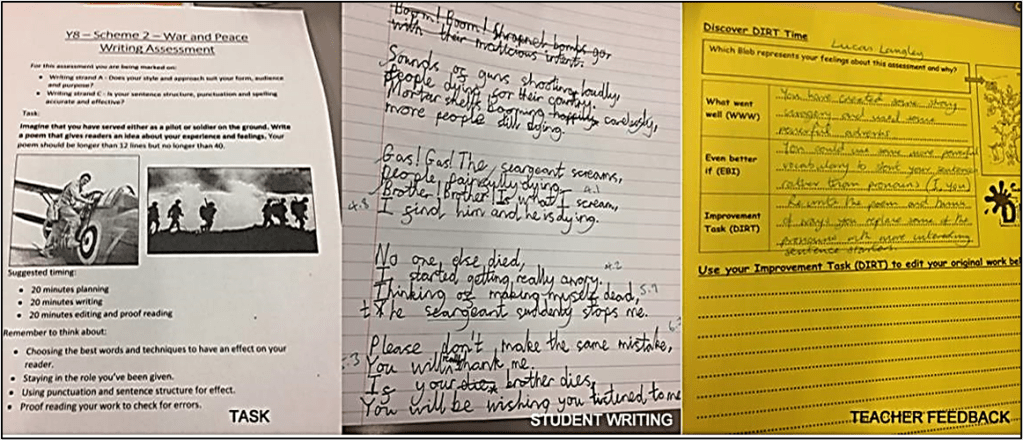

Student responses to teacher feedback in D.I.R.T sessions are required in a form that ‘readily translates into performance indicators…’ (Bernstein, 2004, p213) as is shown in the example above. Instead of students choosing to focus on self-identified misunderstandings or failings, the teacher uses a set of assessment criteria (see teacher feedback in the picture) to produce a list of weaknesses which the student is encouraged to address on a pro-forma. Teachers themselves identified D.I.R.T lessons as ‘hard work’ because of the constraints imposed by the assessment criteria and the formulaic nature of the activity.

“…students need to know where they are, how they’re learning… how they’re achieving, what they need to do to improve but do they actually need a form for them to write it down, for them to get a green pen out and to respond to something I’ve said that… do they actually need that?”

Teacher interview (unpublished doctoral thesis), Dunnett (2021)

Reflection in digital gaming

In contrast, I will describe a reflection process common to many digital games.

Replay is an affordance offered by most digital games, which is widespread and accessible, giving players the opportunity to learn both from their own mistakes as well as the expertise of others. A ‘replay’ visually captures past actions performed by the gameplayer who can choose to watch the replay at a time of their choosing, can slow it down, stop it at certain sections and repeat them until they have worked out where they went wrong. They can also watch other game players play the same section of the game and learn from different approaches to the same task. I would emphasise the agency of the student here in identifying strengths in others gameplay (or work) as well as their own weaknesses. I would suggest that such experience increases the likelihood of a growth in self-efficacy. Rather than passively receiving written feedback based on assessment criteria, they are able to implement these new ‘strategies’ in their next game play session, in a multi-modal form.

I am not arguing that teacher feedback in school activities is not required – clearly it is a necessity, but I am arguing for an increase in opportunities for students to identify weaknesses outside of the assessment criteria – weaknesses they are motivated to improve. For example, in the lesson I observed on war poetry, which was discussed earlier, one student identified the need for more dramatic vocabulary and spent the lesson testing out his new vocabulary ideas on fellow students. Having established their effectiveness on a real audience, he took great joy in including them in his amended poem.

The way forward

Feedback and student reflection on learning seems to have taken on a high level of standardisation and repetition in many schools. Unlike games, where feedback is specific, visual and in-the-moment, reflection on learning in schools tends to consist of standardised and formulaic written responses, overly focussed on material elements such as pen colour and proformas and the de-contextualised reference to assessment criteria, with the potential to render the process meaningless.

More flexible and imaginative ways to reflect on learning are essential, such as the greater use of peer feedback, audio-recorded responses by teachers, model answers and online synchronous commenting on draft work, as well as the usual verbal feedback in lessons. Effective peer feedback relies on the creation of learning spaces where peer support and collaboration are normalised and valued which requires a greater tolerance for chatter and the acceptance that silence is not required in every lesson.

Feedback on work produced should not always be tied to assessment criteria either, but to the impact it creates. For example, in English there has always been a tradition of writing for real audiences on blogs and encouraging feedback from the wider public. International blogging initiatives such as Clusterblogging.net (see Twitter feed for @deputymitchell) both motivate and increase student achievement in writing. In Design Technology, artefacts can be created for use in school, with feedback from users, in the form of popularity and uptake in the use of a manufactured object.

The lack of external assessment, in the form of formal examinations and tests over the past year have given us the perfect opportunity to think again about our classroom practices and share new ideas about how to make the process more effective and motivating for both teachers and students.

“…I just find them (D.I.R.T lessons) hard work… its hard work to engage students on a feedback style …cos it’s so black or white with what we’re feeding back on… you put, it was wrong, this is what you should have put. I don’t think they learn anything by writing it down in green pen.”

Teacher interview (unpublished doctoral thesis), Dunnett (2016)

References

Bernstein, B., 2004. The structuring of pedagogic discourse. Routledge.

Mansell, W., James, M. & Group, A. R., 2009. Assessment in schools. Fit for purpose? A Commentary by the Teaching and Learning Research Programme. In: Economic And Social Research Council, T. & Programme., A. L. R. (eds.). London.

Page, D., 2017. The surveillance of teachers and the simulation of teaching. Journal of Education Policy, 32, 1-13.

Torrance, H., 2017. Blaming the victim: assessment, examinations, and the responsibilisation of students and teachers in neo-liberal governance. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 38, 83-96.