I try to read a range of education blogs and follow a variety of different education accounts on Twitter. It is never helpful to exist in an echo chamber, where your own views are constantly reflected back at you. I’m always willing to learn from other people’s experience and consider new ideas. However, like most people, I do tend lean towards a particular philosophy of education. This would generally be labelled as ‘progressive’ by those on #edutwitter who like to have labels for the differing perspectives which are voiced.

It would come as no surprise then, that I frequently disagree with Tom Bennett, the Behaviour Advisor for the DFE and founder of researchEd, However, I have read his latest book, ‘Running the Room’, which unlike Tom’s tweets, is balanced, good-humoured and for me, surprisingly child-centred. I mention this because I have no problem with alternative views on behaviour and schooling and I do believe in managing behaviour – any community, and schools should be just that, a community of learning – needs to manage the behaviour of participants, be they teachers, students, support staff and so on.

I would also mention, because there is a tendency on #edutwitter to dismiss those who appear to be academics and not practising classroom teachers, that I was an English teacher for 23 years before I stepped away to do some research and work in classrooms in a different role, as a digital education consultant in a wide variety of primary and secondary schools. My thesis, completed in October 2020, involved 9 months of in-depth observation and interviews with students and teachers in a large secondary school, so I have worked with ‘average children in the real world’ (Bennett, 2021)

My perspective on Tom Bennett’s review of Radio 4’s ‘Future Proofing our Schools’ (24th March)

I’m writing this commentary on Tom Bennett’s ‘review’ (or rather opinion piece) because for me it summed up everything that is wrong with the current polarisation of educational philosophy – you are either a progressive or a traditionalist, a proponent of Victorian-style education or 21st century skills and technology. In my experience, very few teachers are solely in one camp or another because ultimately most teachers are pragmatists. Most teachers want what’s best for their students and what can be made to work in the classroom.

It was disappointing, therefore, that Bennett reinforces this unhelpful polarisation by beginning his review of the Radio 4 programme, ‘Future Proofing our Schools’ by using very emotive and hyperbolic language, to characterise the subject matter of the programme as ‘the Cult of 21st century skills’. The very term ‘cult’ conjures up ideas of mindless, unthinking groups of people, led by dangerously charismatic individuals. Not only is this insulting to people such as the very thoughtful contributor to the programme from Agora, Rob Houben, it hardly leads us to hope that this ‘review’ is going to be a balanced one!! The rest of the review continues to resort to such emotive and hyperbolic language with phrases such as ‘open plan fun factories with no teachers, subjects, or tests’ and ‘you condemn them to the circumference of their imagination, which contrary to romantic speculation, is not infinite, but is cruelly circumscribed by the edges of one’s experience’.

I suppose I was expecting Bennett, who after all runs an organisation focusing on educational research, might have discussed a subject such as the future of schools with a little more attention to educational theory and research, in his consideration of the ideas which were raised in this Radio 4 programme.

For me, the key issues which were raised, both by the programme and by Tom Bennett were these:

- Is schooling the same thing as education?

- What is the purpose of education?

- What is the optimum size for a secondary school?

- What should the role of the teacher be?

- Should learning be ‘situated’ in experience or taught in a linear, sequential manner in an age-related manner?

Much of the Radio 4 programme and Bennett’s review was concerned with schooling. The dictionary definition of schooling is ‘education received at school’ or ‘training’. Education, on the other hand, is variously defined as ‘the process of receiving or giving systematic instruction’, ‘an enlightening experience’ (Cambridge Dictionary’ and ‘the cultivation of learning’ (infed.org). Schooling is the structural means by which we involve children in formal education and training. However, education and learning can happen anywhere, at any stage in an individual’s life. Houben (from Agora) refers to this in the phrase ‘lifelong learners’.

Tom Bennett spends some time refuting the critique of formal schooling, the so-called ‘factory model’ which he says is perpetuated by ‘…people who are unfamiliar with what education is like’. I suspect the ‘people’ he is referring to are academics like me, in the field of education, who are, of course, not familiar with education because only currently practising teachers can be familiar. The fact that many education academics were formerly practising teachers is often glossed over. It should also be pointed out that Bennett himself, whilst arguing against a ‘factory model’ uses adjectives which seem strangely akin to such a model such as ‘efficiency’ and describes schooling as scalable models, in the way that an industrial process might be.

It seems to me that if Bennett can suggest that considerations of future education are the ‘same tired tropes’ it could equally be suggested that his model of classrooms, teachers, direct instruction and examination as assessment are similarly tired. Education has changed with technology. Socrates and Plato taught orally – students listened, memorised and discussed. Pens and tablets came along – education adapted. Similarly, in the 20th century, computers and digital tools became available but education, instead of adapting, resisted, for some time and to some extent continues to resist. And here we come to the purpose of education. Are we preparing our children for the world they will live in? Are we creating life-long learners? What should be the aim of schooling?

The Agora school in the Netherlands is clear that it is aiming to create life-long learners, through situated and highly personalised teaching and learning. It can do this because there are only 250 students and they are already 12-18 years old. Most of them will have acquired the basic tools they require (reading, basic Maths) for the challenges and projects the school uses to structure learning. ‘Most’ is the key word here – as one of the contributors of the programme pointed out, this sort of schooling could widen inequalities and existing gaps in knowledge. She also suggested that this situated, personalised model would suit some sorts of students over others. These are legitimate concerns, ones which would need exploring and addressing but surely not a reason to dismiss this model out of hand?

Other issues to consider are ideas about how and by whom the curriculum should be selected, structured and sequenced. I have much sympathy with the concept of fairness and the subsequent conclusion that in order to achieve this, the curriculum should be standardised. However, the way children learn and acquire knowledge within the curriculum does not have to be standardised. Why do all children have to learn the same thing, at the same time and at the same age? We know that children learn and develop at different rates. Does all knowledge need to be chronological and sequential?

“…it’s very hard to understand a bit of e.g. physics without understanding all the physics that led up to that bit”

Bennett, 2021

In order to understand this better it’s useful to look at Bernstein (2004) who approaches education through the lens of pedagogic practices, which order knowledge in particular ways, either to be dependent on market forces or upon the ‘assumed autonomy of knowledge’ (p.196). He defines two types of generic pedagogical practices he has identified which order the transmission of knowledge: visible and invisible pedagogy. Visible pedagogical practices have an explicit regulative and discursive order and emphasise the performance of the student and the ability of the texts they create to satisfy criteria whereas invisible pedagogy has implicit regulative and discursive rules and emphasises acquisition and competence. Bernstein (2004) points out that

The explicit rules of selection, sequence, pace, and criteria of a visible pedagogy readily translate into performance indicators of schools’ staff and pupils, and a behaviourist theory of instruction readily realizes programmes, manuals, and packaged instruction. (p.213)

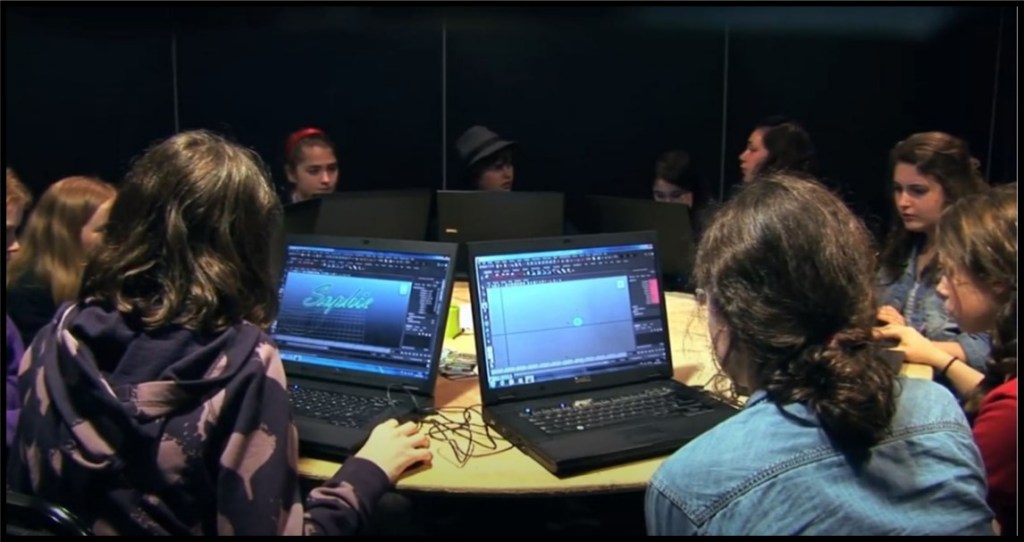

As a contrast, in the research for my PhD thesis I had some experience of the sort of situated learning advocated at Agora school in the Netherlands. In my role as an educational liaison and consultant for Games Britannia, a schools’ video-game festival I observed a number of workshops provided by game industry professionals, particularly on coding and game design development. One of these workshops used challenging mathematical concepts, usually associated with Advanced Level studies in Mathematics, during an exercise to teach 11-13-year-olds how to animate a bouncing ball. This sort of experience would have been an unlikely occurrence in a classroom, where introduction of concepts follows a linear, sequential and predictable pattern, but the inclusion of such a high level of challenge in a learning experience would usually be associated with risk of misunderstanding and disengagement.

However, because the context of such learning was the development of game mechanics, this did not seem to be the case, as the facilitator/teacher and a participant in the session confirm in these quotes from a video interview :

We did a simple physics workshop where we did Newtonian mechanics… so they wouldn’t have known they were doing Newtonian mechanics …but that is what they were doing.

Lindsay Fallow (Stray), Games Britannia workshop, June 2013

We’ve been making a bouncing ball…it was really hard at first but then once you know how to do it, it’s easier.

Student in Lindsay Fallow’s workshop, Games Britannia, June 2013

The active participation of students in the learning process and the immediate feedback of the ‘bouncing ball’ appeared to produce high levels of engagement in this challenging learning experience. Yes, I hear you argue, but did the students understand what they had learnt and how it fitted into subject knowledge? Rob Houben (Agora) points out that the role of the teacher is to point out what the student has learnt – in this case, that the bouncing ball exercise was in fact Newtonian mechanics and part of Physics. The teacher’s role is to scaffold, contextualise and help students to make the connections

This brings us to the final two issues – the role of the teacher and the level of student agency and autonomy which might be desirable in the schooling experience. Simliarly to Biesta (2013) I am not arguing here for the replacement of teaching with learning, I argue that students should learn from teachers rather than be taught by them.

Bennett is rather scathing about the whole idea of student agency and autonomy

“Much of the Agora behaviour policy was based around the idea that we should trust children to direct their own behaviour… good luck with that. The myth of the ideal child is not, it seems, a myth for some.”

Bennett, 2021, Blog post

From my own doctoral research, a number of interesting ideas emerged about the effect that the student-teacher relationship has on the student experience and motivation. Formal schooling tends to produce hierarchical relationships between student and teacher and between formal and informal learning. This polarisation makes it difficult for students to make links between knowledge from out of school and knowledge acquired in school and for them to value their own knowledge in relation to that of the teacher.

In invisible pedagogy (Bernstein, 2014), as espoused at Agora, the school in the Radio 4 programme, students learn from teachers – although control is implicit, the teacher still makes the judgement about what needs to be learnt and when but can adjust and steer this to suit the student. This is what Peter Hyman, a contributor to the Radio 4 programme refers to when he mentions students being ‘apprentices’.

Visible pedagogy, espoused by Tom Bennett, has rules which readily translate into performance indicators and standardised schemes of work but can result in an over-emphasis on target-setting, written feedback and interventions. Where visible pedagogy predominates, agency stays largely with the teacher and participation by students takes the form of exam performance and the production of texts which satisfy assessment criteria. The focus in the classroom is on the behaviour of students and how to control that behaviour so that teachers are able to make the most efficient use of time and space and achieve the goal of good exam results. In order for this to occur power relations need to favour hierarchical relationships between teachers and students. Student participation becomes what Biesta (2015) calls pseudo participation when activity is set and controlled by others. Such relations tend to become demotivating for students.

My research findings suggest that it might improve student motivation and experience of learning if adult-child relations were sometimes less hierarchical, with regular opportunities for students to exhibit their own expertise, particularly around the use of ubiquitous technology such as mobile phones and tablets and to develop their own interests as the students at the Agora school do. In this way students could be encouraged to make links between their out-of-school and in-school knowledge and to evaluate alternative sources of knowledge such as Google and YouTube. As Hampson, Patton and Shanks (2013) point out, by taking students’ views into account schools can:

…help students to work in complementary ways alongside teachers, enabling them to play a more active part in shaping their own education and that of their peers (p.17)

Bennett concludes his review with this rather pessimistic statement about students and educationalists who don’t agree with him:

“Pretending that they (students) are some kind of innately altruistic beings who willingly self-direct their learning and behaviour towards the greater good is a fantasy that can only be sustained by people who have never worked with average children from the real world.”

Bennett, 2021

I can’t help feeling, both from this statement and from what he says in his book ‘Running the Room’, that Bennett’s cynicism is that of the reformed or re-constituted progressive and yes, the romantic. I’m calling for us to avoid that kind of dismissive comment and instead to keep the debate open. Let’s try to avoid reductionist views of education and educational practices. Let’s keep talking about, considering and exploring possibilities such as those raised by the Radio 4 programme. For example, should we be looking seriously at smaller schools? Should we be pursuing more personalised approaches to education rather than the one-size fits all ages and all children approach which often widens the inequality gap. How can we enable more personalised approaches? Perhaps through the sort of digital and blended experiences we all tried out during lockdown?

I look forward to lots of new thinking and debate!

REFERENCES

Bennett, T., 2021. Why The Schools Of The Future Are The Schools Of The Past: My Review Of Radio 4’s Future Proofing Our Schools

Available at: http://behaviourguru.blogspot.com/2021/03/why-schools-of-future-are-schools-of.html [Last accessed 26/03/21]

Bennett, T., (2020) Running the Room: The Teacher’s Guide to Behaviour, John Catt Educational Ltd.

Bernstein, B., 2004. The structuring of pedagogic discourse. Routledge

Biesta, G. J., 2013. Giving teaching back to education: Responding to the disappearance of the teacher. Phenomenology & Practice, 6, 35-49.

Biesta, G.J., 2015. Beautiful risk of education. Routledge.

Hampson, M. Patton, A & Shanks, L., 2017. 10 Ideas for 21st Century Education, Innovation Unit. Available at:

www.innovationunit.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/10-Ideas-for-21st-Century-Education.pdf [Last accessed: 4/06/20]

Positive Thinking, Future Proofing Our Schools (2021) BBC Radio 4, 25th March, 2021

Available at: BBC Radio 4 – Positive Thinking, Future Proofing Our Schools [Last accessed: 26/03/21]