In the past few months, some teachers and educational commentators in newspapers and on social media such as Twitter, have called for a re-assessment of the way that children learn, after arguably the biggest upheaval to traditional schooling since the two World Wars in the early 20th century. The calls for a radical re-think of educational practices have ranged from suggesting a complete overall of the curriculum and the assessment regime, to changing the way we ‘measure’ engagement. One thing is for sure, these enforced periods of online learning have changed teaching and learning practices, whether we think this has been for better or for worse. In this post I argue that we should take this opportunity to embrace new ways of understanding educational practice, retaining what has been learnt during this period and re-evaluating some of our former pedagogical practices

Over the course of the three COVID 19 lockdowns, in my role as a digital education consultant, I have supported a small multi-academy trust in the Midlands, which comprises twelve primary schools and two secondary schools. My expertise in digital education has been built over the course of a 23-year career as an English teacher and curriculum leader in secondary and tertiary education and 5 years of working as an educational technology consultant in a large group of secondary schools in South Yorkshire. To support this practical experience, I recently completed a doctoral thesis which explored the links between boredom and disengagement from learning and teaching and learning practices in schools, Throughout my career, however, my primary interest and motivation has been the everyday teaching practices of classroom teachers and their relationship to educational technology.

The Trust I have been supporting has 12 primary schools who have embraced online learning with varying degrees of enthusiasm. Even in the first lockdown in 2020, some teachers immediately grasped the new possibilities of the remote, online environment. Schools that avoided the direct transferral of in-person teaching and learning practices online i.e. timetabled days of ‘live’ lessons, have been able to take advantage of a wider range of temporal and spatiality possibilities.

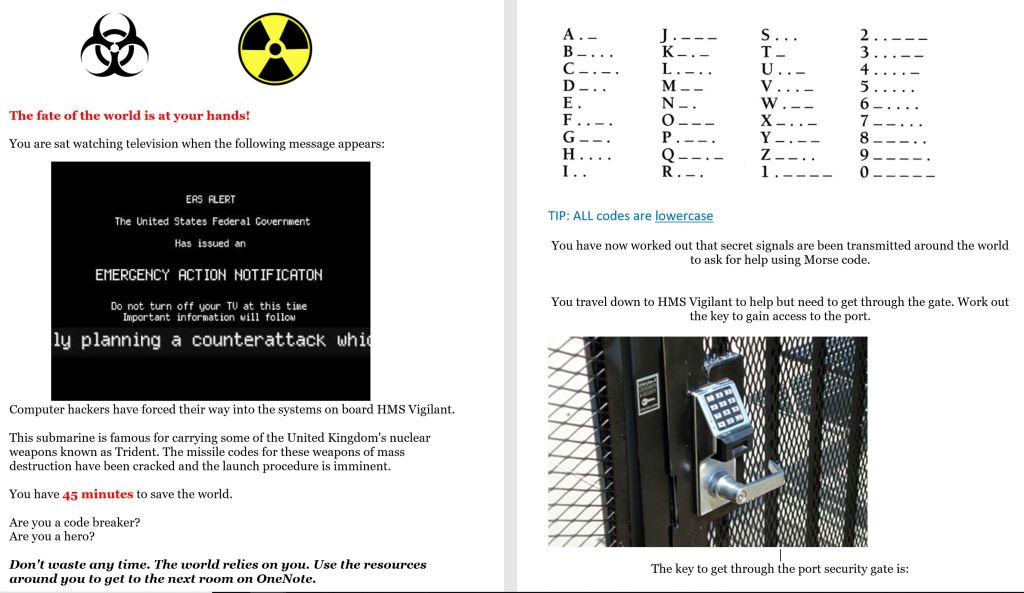

Rather than attempting to reproduce ‘school’ online, replicating the timetable, rules and routines of their physical school, some teachers gave their students a ‘menu’ of learning each day. This menu approach recognised that time, space and access to devices such as laptops varied hugely. Is it really necessary for all students to learn the same thing, at the same time and the same pace, if we have dispensed with the physical classroom and the traditional school day?

For many years schools have been organised on the assumption that all students should be learning the same thing, at the same time and roughly the same pace, within one classroom1. Online learning has turned this on its head – for some teachers and students at least. Yes, there have been schools who have simply replaced like for like – whole days of ‘live’ lessons, as close to an exact replica of the physical classroom as possible. I believe these schools have missed a trick. Schools which have taken a more varied approach have reaped the dividends. By recording lessons, rather than making them all live, for example, you give students the ability to stop, start and replay your teacher input. The lesson can remain on your online platform for review. Students’ ability to manipulate lesson content has been associated with increased engagement with that content2. In many schools, content has been uploaded for students to access at their leisure and to edit at will to suit their own purposes. In my own MAT for example, OneNote Class Notebook has been used to distribute copies of worksheets and information, where it is stored in their own personal ‘exercise book’ and where students and teachers can access, edit and comment on it. Gone are the days of ‘the dog ate my homework’ or ‘I didn’t get the worksheet Miss’. Admittedly in some cases that has been replaced with ‘I can’t access the files from my phone’ or ‘My Wi-Fi doesn’t work’!

Online learning has changed the traditional dynamic of highly regulated physical space. Instead, education spaces such as classrooms are constructed through relations between social and material actors – students, teachers, technology, objects and environment. As Burnett (2013)3 describes, the concept of classroomness – a ‘mesh of practices’ is created in the online space, where official and unofficial spaces exist simultaneously – breakout spaces, chat, the home environment, the school classroom, YouTube and Oak National Academy and so on.

In such spaces, there is no need to construct elaborate seating plans to separate Johnny from best mate Matt, to stop Milly throwing her pen at Faizah or engineer ability groups to work together. Everyone is ‘facing the front’ in Google Classroom and Microsoft Teams, with students in a neat grid on the screen but in reality, can physically be in any position they choose from lounging on the bed, to sitting at the dining room table. Noise, another bug bear of physical classroom teaching has become a thing of the past. Teachers can mute any student speaking out of turn or all students during teacher presentation. All students can ‘see the board’, in the online PowerPoint presentation – assuming they have a device and managed to get online at all!

Concentration and the ability to pay attention have long been considered to be measures of behavioural compliance and essential for learning. School rules are inherently spatial – they control bodies, movement, talk, noise, learning, space and time and tend towards uniformity and standardisation. Much of this regulation is aimed at controlling children’s behaviour rather than directly affecting learning or pedagogy. So, does regulating time and space result in higher concentration and improved learning? There is good evidence that distraction, whether that be through visual stimulation or other sources, can affect concentration and learning. One might expect distraction to be a bigger problem in the home environment than in a school classroom. However, that has not necessarily been the case. Because students have been able to engage with the teacher and the lesson material at different times, of their own choosing, to access multi-modal information, it has been possible for students to engage with material in different ways and for differing lengths of time, reducing the likelihood of inattention.

What has emerged from my observation of both in-person, physical classrooms and online learning spaces is that the organisation and regulation of time and space has a big effect on the affective experience of students. High stakes assessment and the need for predictable outcomes have dictated the use of timetables and seating plans to regulate the relations between student, teacher, resources and space. Online learning has increased the mobility of these elements and different affective dynamics have been created.

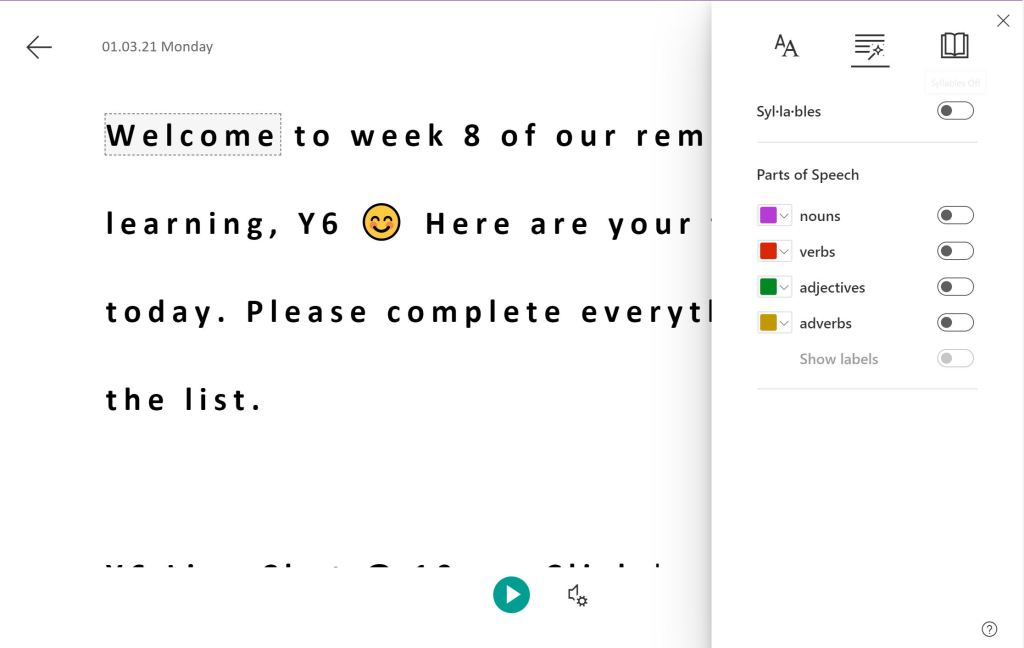

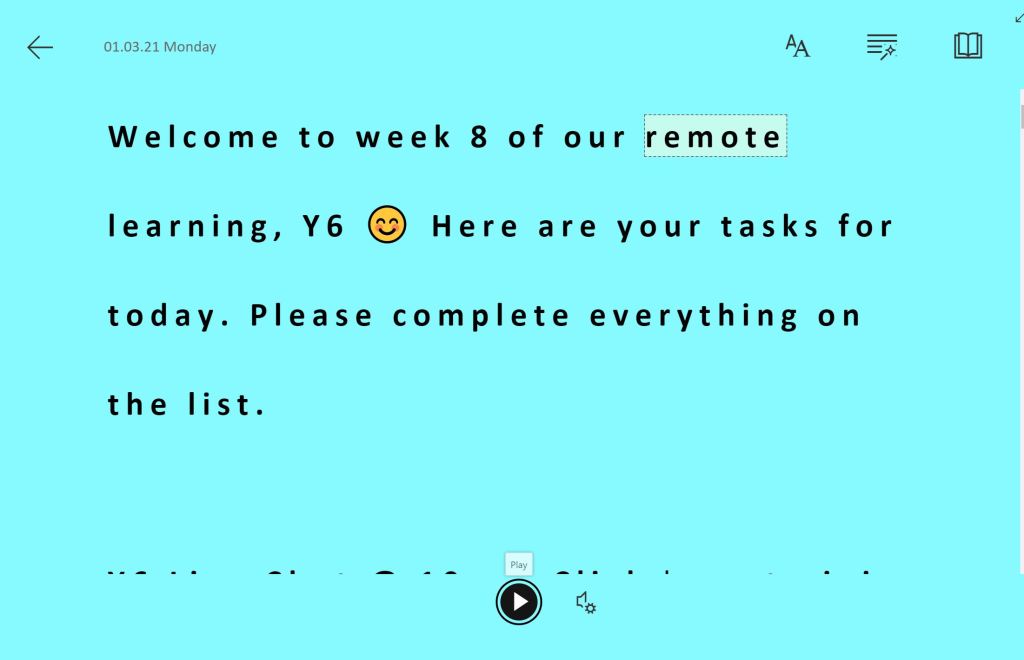

So, what are the takeaways from online learning? In many cases student agency has been increased as they have been expected to take a role in managing their access to resources, whether that be the pace at which they consume content or the way they personalise it so that it makes sense to them. An example of this is the use of the accessibility tools such as Immersive Reader in OneNote Class Notebook where students can apply a filter to a text, get the text read aloud or broken down into manageable chunks at the touch of a button, something not possible without considerable graft from their teacher in the physical classroom.

By being able to choose how to use of their own time, necessarily repetitive activities such as practising examples in Maths can be spread out over the whole day. The ability to choose how to use their own physical space has meant that reading can be done in a comfortable chair or lying on a bed. Ask yourself when was the last time that you read for pleasure, sitting at a desk?! Reading can also go on as long as the student wants rather than being artificially cut short, as we often have to do, to make reading fit within the school timetable.

Activities which we might have liked to do in the classroom but which just take up too much time and disrupt the school day, such as collecting samples of grass, worms, or household materials can now become part of an online learning experience, with students taking pictures or filming themselves and feeding back in a ‘live’ video call.

Participation in online lessons has not been restricted to handwritten texts – students have submitted video footage of them performing tasks, teachers have included home learning such as baking a cake, in their ‘lesson’. We can assess understanding of a process such as collecting samples or executing a football skill by watching rather than reading a report of the activity.

My own research findings suggest that when adult-child relations are less hierarchical, as they have often been online, there can be regular opportunities for students to exhibit their own expertise, particularly around the use of ubiquitous technology such as mobile phones and tablets and to develop their own interests and expertise. Students have been encouraged by their teachers to make links between their out-of-school and in-school knowledge and to evaluate alternative sources of knowledge such as Google and YouTube.

Of course, returning to face-to-face learning and the physical classroom will be an enormous relief to both teachers and students. For most students, nothing can replace the social and educational experience of the physical classroom. For others, I have heard many examples of quiet, withdrawn students blooming in the online environment, even taking the lead in online discussion and activities. I have my own personal teaching experiences of this phenomenon too. More time to think and respond, less likelihood of another student talking over you or answering more quickly perhaps?

My own doctoral research has suggested that incorporating a more social and material approach to understanding educational practices might be helpful, particularly after the past year of COVID 19 restrictions. Such an approach encourages us to see schools as networks rather than bounded, stable places or ‘static containers’. Teachers might want to incorporate what has been learnt from online learning practices, to look beyond the usual distinctions between formal/informal learning and in and out of school practices in order to re-evaluate the whole experience of learning in the classroom,

References:

- Bielaczyc, K. and Collins, A., 1999 Learning communities in classrooms: A reconceptualization of educational practice. Instructional-design theories and models: A new paradigm of instructional theory, 2, pp. 269-292..

- Jewitt, C., Moss, G. and Cardini, A., 2007. Pace, interactivity and multimodality in teachers’ design of texts for interactive whiteboards in the secondary school classroom. Learning, Media and Technology, 32(3), pp.303-317.

- Burnett, C., 2014. Investigating pupils’ interactions around digital texts: A spatial perspective on the “classroom-ness” of digital literacy practices in schools. Educational Review, 66(2), pp.192-209.